QUICK LINKS

History of the South Bay of Los Angeles Through 1900 Palos Verdes Secrets and Little Known Facts History of Palos Verdes Estates History of Rancho Palos Verdes History of Rolling Hills Estates and Rolling Hills History of Manhattan Beach History of Hermosa Beach History of Redondo Beach History of El Segundo History of San Pedro History of Torrance History of Lomita Seaview Landslide Information

History of the South Bay of Los Angeles Through 1900

BY BRUCE AND MAUREEN MEGOWAN

Native Indians

While first described in 1542 by Portuguese Explorer Juan Cabrillo, for almost three centuries the Palos Verdes Peninsula remained undisturbed and the exclusive domain of the local Indians, whose artifacts are still being unearthed. The most recent Native Americans to live in Palos Verdes were members of the Tongva tribe who spoke a Shoshone language. The Tongva did not use a written language, but their myths and their superb knowledge of their environment were passed down from one generation to the next through storytelling and teaching. Large trees did not grow in this part of California, so they built houses with frames made of willow poles. The willow frames were covered with bundled reed called tule. The Tongva people also used large redwood logs that drifted in on the tides from the north to make dugout canoes. They also constructed reed boats, and sealed them with tar or asphalt found on the beach. The Spaniards called the native people after the names of nearby missions. The natives in the Los Angeles area became known as the Gabrielino, because they were the closest to the Mission San Gabriel.

During the summers, the Tongva camped along the ocean and hunted in places such as Abalone Cove for fish, seals, sea otters, abalone, and other shellfish using their canoes. During the cold, rainy season, they moved back to base camps on higher ground and hunted deer, rabbits and squirrels. The Tongva held many beliefs that helped them to understand the world around them. They worshipped one god called The-Giver-of-Life. They believed that The-Giver-of-Life had placed the world on the shoulders of seven giants. Whenever the giants moved, it caused an earthquake. They also believed that dolphins were responsible for swimming around the world to guard its safety.

Indian Artifacts from Palos Verdes (picture 4/3/26)

For over two hundred years after the first explorers came, the Spaniards occasionally met and traded with the Tongva people. In the late 1700’s, the Spaniards began to permanently settle the Palos Verdes Peninsula area. As they moved in with their cattle and horses, and new crops, the native animals and plants that the Tongva relied on for their survival began to disappear. The Spanish began to persuade the Native Americans to give up their old way of life and move to the Spanish missions and ranchos, where they would learn farming and cattle raising.

Portuguese explorer, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, while sailing under the flag of Spain, was the first European to set eyes upon the barren hills and plains of what was to be Rancho San Pedro. On October 8, 1542 he sailed into San Pedro Bay. There, he noticed several wild fires burning in the surrounding hills producing dark plumes of smoke. He named the area “Bahia de los Fumos” which was Spanish for “Bay of Smokes”. This bay with a shallow estuary held this title for over fifty years, until changed by another Spanish sea faring explorer. On November 26, 1602, Sebastian Viscaino sailed into the same bay and renamed it Ensenada de San Andres (Bay of Saint Andrew), mistakenly thinking he arrived on the feast day of Saint Andrew. In actuality he entered the bay on the feast day of Saint Peter, Bishop of Alexandria. In 1734, Cabrera Bueno, a famed navigator and cosmologist discovered Vizcaino’s error and renamed the bay San Pedro, in honor of the martyred saint. Today, the port community of San Pedro still retains the name.

Two points along the coast bear very old names. In 1793 Captain George Vancouver, who had been commissioned by King George III of England to explore and chart the Pacific coast, sighted a “very conspicuous promontory”. He named it Point Vincente, after the friar Padre Vincente Santa Maria stationed at the MIssion San Buenaventura. The spelling of the name was revised from Vincente to Vicente in the mid 1920’s. (The United States Government established a lighthouse on Point Vicente in 1875, and the present structure was built in 1926). Sailing a little further south along the coast, Vancouver came to a second point which he named Point Fermin, in honor of Padre Fermin Francisco de Lausen, president of all the California missions.

The vessels that traded at San Pedro anchored at a point on the northwest side of San Pedro, slightly northeast of Point Fermin, off the coast of Rancho Palos Verdes. Though later known as Timms’ Point, this anchorage was first called Sepulveda Landing. Between Point Fermin and Point Vicente lies Portuguese Bend, named for Portuguese whalers who used the cove for a rendezvous and a whaling station. The name Portuguese Bend comes from the whaling activities of Portuguese whalemen from the Azores. An Azorean shore whaling captain named José Machado brought shore whaling to this bend in the coastline north of San Pedro Bay after the closure of the San Pedro Bay whaling station on Deadman’s Island in or about 1862. He brought with him a crew of Azorean whalemen. Whaling activities were believed to have taken place here up until about 1884. Portuguese Bend was also a smuggler’s hideaway. Spain limited the number of ships which could dock in San Pedro, and exacted stiff fines including forfeiture of property and death to those who violated the edict.

Rancho San Pedro ( The information on Rancho San Pedro and Rancho de los Palos Verdes following was obtained primarily from the excellent book “Palos Verdes Peninsula: Time and the Terraced Land” by Augusta Frank, and several other sources cited below )

The land which includes the entire Palos Verdes Peninsula, San Pedro, and parts of Wilmington was part of the first Spanish land grant in California. Juan Jose Dominquez, a member of the 1769 Spanish Portola Expedition to Alta, California, stayed in Alta as a peace officer and guide. He helped protect Junipero Serra and other Franciscan padres who established a chain of missions from San Diego to Sonoma. In September 1782, Pedro Fages, the military commandante of California, became the Provincial Governor of Alta California. He was Dominguez’s former lieutenant and accompanied him during the Portola Expedition of 1769. While Fages visited San Diego in 1783, Dominguez sought an opportunity to make a request for property from his former commander, who had become a powerful and influential official. Dominguez petitioned for some vacant land south of the pueblo of Los Angeles.

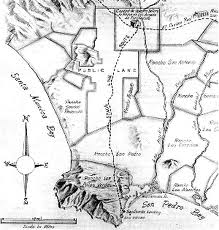

Due to Dominguez’s many years of dedicated service to the King of Spain, Governor Fages bestowed a provisional grant to the retired old soldier in March 1784, allowing him to graze his cattle on Rancho San Pedro. These original land grants were not considered at the time to be a permanent ownership interest, but were instead merely considered a permit to use the land and to occupy it. This was the first private land grant in Southern California. Rancho San Pedro stretched from Compton to Redondo Beach and Long Beach, and included the Palos Verdes Peninsula. The boundaries of this original land grant have been a controversial subject of historians, with most historians stating that the Rancho San Pedro consisted of approx. 75,000 acres (which were later documented by surveys in 1817, 1853, and 1855 ). An early map exists which shows the northern boundary of the Rancho San Pedro extending due west from its northeasterly border with the Los Angeles River, coinciding with the earlier southern border claimed by the Pueblo de Los Angeles. which would have included approx. 90,000 acres, including what later became known as Rancho Sausal Redondo, as well as the present day cities of Manhattan Beach, Hermosa Beach, and El Segundo. Later surveys, however, fixed the northern boundary of Rancho San Pedro as extending in a southwesterly direction to the ocean at a point between Redondo Beach and Hermosa Beach.

After the death of Juan Jose in 1809, Manuel Gutierrez, who had been the ranch manager of the Dominquez ranch, became the executor of Juan Jose’s estate. In his will, drawn up three days before his death, as Juan Jose Dominguez had no wife or children, he left half of Rancho San Pedro to Cristobal Dominguez and the other half was divided between Mateo Rubio, who had been in charge of ranch operations, and Gutierrez.

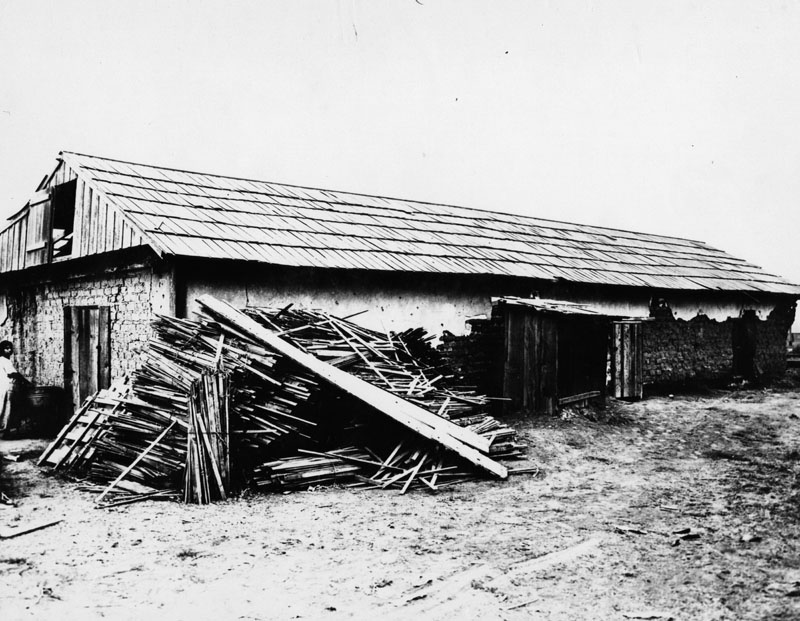

Original Adobe of Juan Jose Dominquez (1912 photo courtesy of California University Dominquez Hills archives)

When Cristobal realized that his uncle died in debt and neglected his rancho, he initially wanted no part of his inheritance. He had no money to pay his uncle’s creditors and could not occupy the rancho, even if he wanted, because he was still obligated to the military. He, in fact, did not even attempt to defend his title to the land for seven years. Gutierrez paid off the debts owed by Juan Jose Dominguez, established residence and assumed control of the rancho.

Rancho de los Palos Verdes

Shortly after Gutierrez assumed control over Rancho San Pedroin 1809, Gutierrez allowed a friend, Jose Dolores Sepulveda, to graze a thousand head of cattle in the southwest portion of the property known as Canada de Los Palos Verdes (Canyon of the Green Trees). (Note: some historical accounts give the name of the original Sepulveda family member claiming ownership rights to the Rancho de los Palos Verdes, as being Don Dolores Sepulveda, instead of Jose Dolores Sepulveda. The use of the name “Don” is a Spanish honorific title given to large property owners to show respect, and the proper use of the term should be Don Jose Dolores Sepulveda). Sepulveda built an adobe home here in 1818 and made significant improvements to the unused portion of the land. Sepulveda’s adobe home (Registered California Landmark No. 383) is located in the Walteria section of Torrance, at Madison Street and Courtney Way.

Jose Delores Sepulveda Adobe built in 1818

Cristobal Dominguez was upset with the arrangement Gutierrez made with Sepulveda and protested the presence of the latter, who happened to be his cousin. It was assumed that Dominguez abandoned his claim to the rancho and that Gutierrez had every right to give young Jose Dolores Sepulveda permission to use the land.

In August 1817, Cristobal Dominguez finally filed a petition with Governor Pablo Vicente de Sola to have Sepulveda removed from the property and request that Rancho San Pedro be fully granted to him by eliminating the ownership rights of Gutierrez and Mateo Rubio. Gutierrez and Sepulveda refused to give up the land they worked so hard to improve. The governor issued a short poignant decree ordering Sepulveda from the rancho and granting provisional ownership to Cristobal Dominguez. Sepulveda refused to relinquish his home and appealed the governor’s decree. On December 31, 1822, shortly after Mexico had gained its independence from Spain, Governor Sola formalized the land grant by confirming Cristobal Dominguez as owner of Rancho San Pedro.

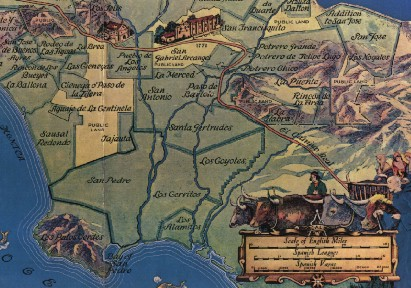

Mexican Land Grants Photo credit: Title Insurance and Trust Company, Los Angeles

After receiving title to Rancho San Pedro in 1822, Dominguez remained in San Diego and never even visited the rancho. His death three years later in 1825 brought about another change in ownership at which time the estate was left to his three sons, under the management of his eldest son, Don Manuel Dominguez (known simply as Manuel Dominquez), then about 20 years of age. Over the next twenty years, he bought out his brothers’ interest in the ranch.

Don Manuel Dominguez was one of the very few citizens of his era to hold public office under both the Mexican and U.S. governments in California. Before 1857, he was elected three times as Acalde (Mayor) of Los Angeles and Judge; he was chosen as a delegate to the convention in Monterey which drew up the first State Constitution, and he later served as a Supervisor for Los Angeles County.

In 1826, Don Manuel constructed the six room Dominquez Rancho Adobe home for his new bride Maria Engracia Cota. The home still stands, and is in excellent condition and can be visited at 18127 Alameda Street, in Carson

Dominquez Rancho Adobe

Sepulveda appealed the 1822 decision a second time and requested a personal meeting with Governor Luis Arguello in Monterey to plead his case. In 1824, while Sepulveda was returning from his trip to Monterey, he was killed in a violent Indian uprising at Mission La Purisima Concepcion, near today’s Lompoc. His oldest sons, Juan Capistrano Sepulveda and Jose Loreto Sepulveda, continued his quest for Rancho Palos Verdes. Jose Dolores Sepulveda also had two other sons and a daughter (Jose Diego Sepulveda, Ygnacio Rafael Sepulveda, and Maria Teresa Sepulveda). Manuel Gutierrez guided the boys and supervised their cattle operations. On May 16, 1826, after the death of his father in 1825, Manuel Dominguez filed a petition with Governor Jose Maria Echeandia to have the Sepulveda brothers and their cattle removed from the Palos Verdes portion of the rancho. On May 26, 1826, the heirs of Cristobal Dominguez were confirmed by the governor as owners of Rancho San Pedro, thus being officially recognized by the new Mexican regime. Echeandia, in 1827, known for his administrative ineptness, also provisionally approved of the Sepulveda’s claim to Palos Verdes

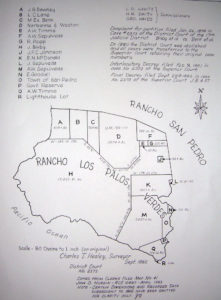

In 1834, a judicial decree was made by Governor Jose Figueroa which was intended to settle the dispute between the Dominquez and Sepulveda famiies, and Juan Capistrano Sepulveda and Jose Loreto Sepulveda were awarded the 31,629 acre Rancho Palos Verdes. Figueroa also stipulated in his decree that Manuel Gutierrez may remain as a resident and free to graze his stock on the rancho for the rest of his life, providing he gave up all claim of ownership to Rancho San Pedro. The partition decree left the Dominguez family with 43,119 acres reducing Rancho San Pedro nearly by half the area of the original grant.

Extent of original grant of the Rancho San Pedro and the Rancho de los Palos Verdes, with present-day city boundaries and streets (note that the eastern boundary was probably the original path of the Los Angeles River) –Jack Moffett

The Sepulvedas were given yet another order to leave the Palos Verdes section of Rancho San Pedro in June 1839. Again, the Sepulvedas defended their title and on April 22, 1841, they received a Decree of Possession and an additional strip of land north of Palos Verdes Hills from Governor Alverado. In June 1841, an agreement was signed by the Dominquez family transferring all right to the Rancho de los Palos Verdes to the Sepulvedas. Then on June 3, 1846, Governor Pio Pico officially confirmed the title of Rancho de los Palos Verdes to the two oldest Sepulveda brothers. Pico also confirmed the title of the balance of the Rancho San Pedro to Manuel Dominguez and the other members of his family.

Juan Capistrano Sepulveda built his adobe home near the intersection of Gaffey and Anaheim Streets in San Pedro at Five points, which is the convergence of the following five streets: Palos Verdes Drive North, Gaffey Street, Anaheim Street, Vermont Avenue and Normandie Avenue. The casa was located on the bluff on the northwest side of this intersection. Possibly the site of the trailer park. The casa overlooked Machado Lake (Bixby Slough) and the site of the Gabrielino village of Suangna. Jose Loreto Sepulveda built his home further south on the west side of North Gaffey Street between Channel Street and Anaheim Street, San Pedro. It was located on the eastern slope of a bluff on the west side of Gaffey Street (possibly on the site of Taper Avenue Elementary School). Jose Loreto Sepulveda was also 2nd Alcalde of Los Angeles, which was basically Vice –Mayor of Los Angeles for 4 years during the period 1837 – 1848. Juan Capistrano Sepulveda was also 2nd Alcalde of Los Angeles in 1845.

On the morning of August 6, 1846, Juan and Jose Sepulveda were at the Port of San Pedro and spotted an American Warship. This ship, commanded by Commodore Robert Stockton, had been sent to San Pedro by President Polk, to seize California in the name of the United States, after hostilities had begun with Mexico on April 25, 1846. The Sepulvedas immediately sent word to General Castro, in charge of the Mexican troops in Los Angeles. On August 11th, Stockton began to march his troops from San Pedro to the pueblo Los Angeles. General Castro, unprepared to defend the city, fled to Mexico, and on August 13th, Stockton rode into Los Angeles without firing a shot.

Stockton, returning to Monterey, left Lt. Gillespie in charge of Los Angeles. Lt. Gillespie proved to be particularly unsuited to command the city, and after issuing a number of very draconian measures, including limiting the right of more than 2 people meeting together and arresting several important citizens for questioning, the people of Los Angeles rose up in rebellion. Lt. Gillespie, on September 24th sent a messenger to Stockton in Monterey to send reinforcements, and then he and his men retreated back to a commercial ship at anchor in San Pedro to wait for the reinforcements.

On October 6th. the frigate “Savannah” arrived with reinforcements. Juan Sepulveda, in charge of a 45 man patrol, saw the arrival of the American war ship, and dispatched a messenger to Maria Flores, Jose Antonio Carillo, and Andre Pico, who were in charge of the forces defending Los Angeles. Flores and Carillo then immediately led their forces to meet the Americans. The Americans first made camp at the Dominquez adobe, and after the Californians attacked them with cannon fire, the Americans began to march towards Los Angeles. The Californians repeatedly attacked the advancing American column, and after a particularly devastating cannon attack, the Americans again retreated to the “Savannah” in San Pedro harbor. The Americans buried their dead on Deadman’s Island in the harbor, and waited for reinforcements. The Sepulvedas were responsible for patrols observing the actions of the Americans,

Bones discovered on Deadman’s Island during the removal of the Island for the construction of the San Pedro breakwater. Photo dated 1928, courtesy of California University Dominquez Hills archives

Deadman’s Island in 1915 from the west side. courtesy of California University Dominquez Hills archives

On October 23rd, the “Congress” sailed into San Pedro harbor with Commodore Stockton and reinforcements. The forces of Carillo and Flores created an illusion of having many more men than they actually had by riding in a circle single file through a gap in the trees in a hill overlooking the harbor, and by dragging brush to kick up dust. Stockton, thinking that he was facing a force of at least 800 men, panicked and immediately set sail for San Diego. The war was far from over, however, as a land force led by Colonel Stephen Kearney was moving across the continent towards California. Kearney succeeded in reaching Stockton in San Diego, and on December 29th, their combined force of approx. 600 men marched up the coast towards Los Angeles.

On the morning of January 9th, 1847, a bloody battle took place overlooking the San Gabriel River, near present day Montebello, between the Californian’s led by Flores, and the Americans, and during the battle, young Ygnacio Sepulveda, the brother of Juan and Jose Sepulveda was killed. The next morning, the triumphant American forces marched into downtown Los Angeles.

On January 11th, Fremont’s men reached the San Fernando Valley. Flores, having fled to Mexico after his defeat two days before, was not able to provide reinforcements to the men led by Carillo and Pico, and when Andres Pico surrendered his sword in a Cahuenga rancho house, California’s participation in the Mexican-American war had ended. on February 2, 1848, the Treaty of Guadeloupe Hidalgo was signed annexing California to the United States.

Continuing fight over rights to Rancho de los Palos Verdes

After the Mexican American War of 1846-1848 granted sovereignty over California by the United States, a Land Commission was formed in 1851 to rule on the validity of conflicting Spanish land grant claims. In later years, descendants of Juan Capistrano Sepulveda claimed that Juan Capistrano Sepulveda and Jose Loreto Sepulveda had executed a Declaration of Trust purporting to have granted an equal ownership interest in the Rancho de los Palos Verdes to all five brothers and sister.

On December 20,1853, title to Rancho de los Palos Verdes was granted to the Sepulvedas. This decision was appealed to the U.S. District Court, which ruled in favor of the Sepulvedas on December 10, 1856, which ruling was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court, on March 4, 1858 finally decided not to hear the appeal. Final title was conveyed in an 1858 land patent, signed by then-President James Buchanan settling the long running dispute between the Dominquez and Sepulveda families. This land patent ceded the Rancho San Pedro totaling approx. 43,000 acres to the Dominguez family, and 31,000 acres of the Palos Verdes Peninsula to the two oldest Sepulveda brothers as the Rancho de los Palos Verdes.

The Partitioning of Rancho Los Palos Verdes

Beginning in 1840, the Sepulveda family began to sell or mortgage a large portion of their interest in Rancho de los Palos Verdes. In July 1840, Ygnacio Sepulveda surrendered his claimed interest to his brother-in-law Nathaniel Pryor for $50. In 1844, Jose Diego Sepulveda exchanged his claimed one-fifth interest in Rancho de los Palos Verdes to Santiego Johnson for Johnson’s interest in Rancho Yucaipa in San Bernardino (although the two senior Sepulveda brothers disputed this land transfer, the heirs of Johnson filed a law suit in November 1853 and gained legal control of the land). Jose Diego Sepulveda still built a home in San Pedro in 1845, and in 1849, Jose Diego Sepulveda sold his interest in Rancho Yucaipa, and in 1853 built the first two story adobe in Southern California on the Rancho de los Palos Verdes (which was razed in 1910). The home was located in the 700 Block of Channel Street (faced Gaffey Street) in San Pedro

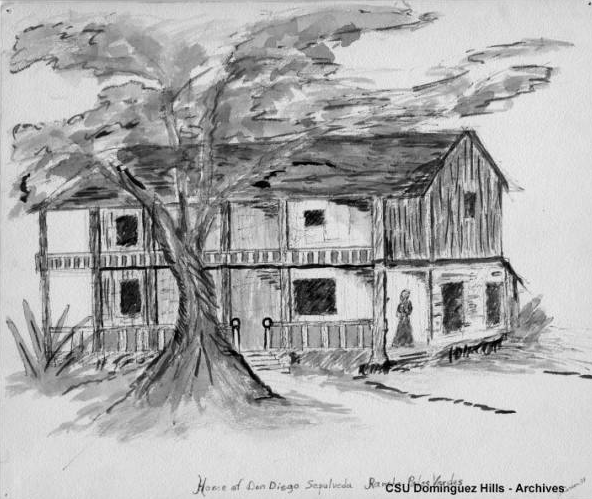

Watercolor of Jose Diego Sepulveda home by John Victor Carson ., courtesy of CSU Dominquez Hills Archives

Jose Diego Sepulveda adobe

During the ten year period from 1855 to 1865, the Sepulvedas incurred significant financial difficulties, including a severe drought in 1862-1864 which wiped out most of their cattle herd. During this time, the Sepulvedas began to incur significant debt. In 1855,Pablo Pryor, the son of Nathaniel Pryor, who had died, filed a lawsuit to perfect title in his claimed two-fifths interest in the Rancho de los Palos Verdes (which included his father’s claimed interest, as well as his mother’s (Maria Teresa Sepulveda Pryor) interest). On May 11, 1855, Juan Capistrano Sepulveda mortgaged his share of the Rancho for a loan of $2,962 at an interest rate of 6% per month! In 1856, he then sold his interest in the Rancho to a man named Lamalfa, who then mortgaged the property, which then went into foreclosure, which was then purchased by Jose Diego Sepulveda, Juan’s brother, for $3,000 in 1858. Jose Diego Sepulveda then deeded 12 acres of land to his brother Juan Capistrano Sepulveda, upon which Juan’s house stood. The home stood at Five Points, San Pedro/Harbor City/Wilmington border.

in 1869, Jose Diego Sepulveda died, and left his interest in the Rancho to his sons, Aurelio, Roman, and Rudecinda. Narbonne & Weston, two sheep herders, bought a 1/10th interest in the Rancho from Jose Loreto Sepulveda for $4,000 in 1872, and later bought 3,700 acres from Juan Capistrano Sepulveda. In December 1872, Jotham Bixby bought the 1/5th interest in the Rancho claimed by Maria Teresa Sepulveda. In August 1874, Jose Loreto Sepulveda mortgaged his interest in the Rancho for a loan of $1,500 by Merchants Exchange Bank of Los Angeles (which later claimed an interest in 2,100 acres), which was foreclosed on in 1879, and then purchased by Jotham Bixby. A.W. Timms had also previously acquired some of the Rancho, and sold 50 acres to Edwin Goodall. In 1874, Bixby purchased the one-fifth interest in the Rancho claimed by the Johnson heirs at a public auction. During these years, Bixby made additional purchases of a portion of the Rancho from Timms. Other accounts have Bixby purchasing part of Pablo Pryor’s claimed interest in the Rancho. In 1875, L.C. Lane acquired 1,100 acres in a tax sale. R. Poggi, the son-in-law of of Jose Loretto Sepulveda also claimed 200 acres. Edward N. McDonald also acquired an interest in the Rancho from Narbonne & Weston, and J.G. Downey also claimed an interest in the Rancho.

Numerous additional lawsuits were filed in the mid-1870’s disputing ownership of the land making up the Rancho de los Palos Verdes and requesting partitioning of the land, and from 1878-1882 the land was held in receivership, even though an additional land patent was issued to the Sepulvedas on June 23, 1880, signed by Rutherford B. Hayes. Sadly, Jose Loreto Sepulveda (who had sold or mortgaged his entire interest in the Rancho) died in 1881, a broken man. Numerous parties claimed an interest in the Rancho, based upon the transactions discussed above, many of them with conflicting claims, sometimes buying or selling the same claimed interest in the Rancho. During the period from 1865 to 1880, the Sepulvedas were engaged in 78 lawsuits, six land partitions suits, and 12 suits over eviction of squatters.

At the conclusion of these complicated law suits on September 25, 1882, Rancho de los Palos Verdes was partitioned into seventeen portions . The largest share, the 17,085 acres which constituted the Palos Verdes Peninsula, was awarded to Jotham Bixby, with only about 12 acres awarded to Juan Capistrano Sepulveda (who died in 1896), and approx. 4,399 acres (most of the town of San Pedro)awarded to the family of Jose Diego Sepulveda (A.W.Sepulveda), his brother.

Partition Map of the Rancho Los Palos Verdes, September 25, 1882—Courtesy of John G. Nordin

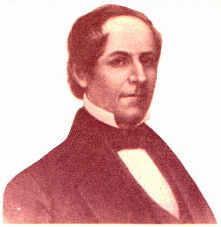

Jotham Bixby 1905

When Don Manuel Dominquez died, also in 1882, with no male heirs, the balance of the Rancho San Pedro was divided among six sisters, Dominquez descendants with names familiar to South Bay residents, such as Del Amo, Carson, and Watson. One of the Dominguez daughters, Susana, married a man named Dr. Gregorio Del Amo (a name familiar to anyone in the South Bay because of the giant Del Amo Fashion Center mall in Torrance). Another Dominguez daughter, Dolores, took a husband named Watson (known today for the Watson Land Company and Industrial Centers). A third daughter, Maria Victoria, married a successful businessman named George Henry Carson.In 1862, Carson became chief assistant to Don Manuel. Victoria Regional Park is named after his wife. The city of Carson is named after George Carson’s son John Manuel Carson.Three of the sisters, Susana, Guadalupe, and Maria de Los Reyes Dominguez, inherited portions of the estate, each including individual sections collectively known as the Ocean Tract.

In 1889 this coastal tract was sold to the Redondo Beach Improvement Company, founded by Robert Thompson and John Ainsworth. They promoted, developed, and sold land that eventually became the nucleus of the city of Redondo Beach, incorporated in 1892. The name of the city is Spanish for “round,” which either refers to the half-round street pattern of the original townsite, or to the adjacent Rancho Sausal Redondo. Some of the Redondo Beach streets named for Spanish women carry the names of Don Manuel’s daughters. Those street names are Catalina, Elena, Francisca, Gertruda, Guadalupe, Helberta, Irena, Juanita, Lucia, Maria, Paulina and Susana avenues.

In 1894, George Bixby took over control of his father’s, Jotham Bixby’s, interest in Rancho de los Palos Verdes. Harry Phillips was hired as Ranch Manager by Bixby, and he became the first resident of the Peninsula. He brought farming to the Peninsula and planted many of the eucalyptus trees. Phillips built his first home on land south and east of the Rolling Hills City Hall and Gate House. He raised over 2,000 head of fine cattle as well as horses and farmed lima beans, barley for hay and grain.

Built in 1910 as the second home for the Phillips family, the ranch was located in Blackwater Canyon to the northeast of the present intersection of Palos Verdes Drive North and Rolling Hills Road in Rolling Hills Estates.

When land values dictated that Peninsula property could no longer be used for only cattle grazing, Bixby leased the land to Japanese farmers, at the urging of Phillips, to cultivate fruits and vegetables. Land was leased for approx. ten dollars an acre, and in the early 1900’s, approx. 40 Japanese families were cultivating crops on the Peninsula. The Ishibashi family was one of the first Japanese families to farm the Peninsula. Kumekichi Ishibashi came to San Francisco in 1895, and walked to Los Angeles. He worked as a houseboy for many years, but in 1906 leased his first farm from Bixby in 1906 at the site of the present day Trump National Golf course in Rancho Palos Verdes. In 1910, Kumekichi brought his younger brother, Tomizo, to join him at the farm. The Ishibashi family used to get water once a week for their house, which they built themselves, from a well in the Portuguese Bend area, and this took the better part of a day. The family farmed by the “dry farming” method with no irrigation, and grew beans, cucumbers, peas and tomatoes. Early electricity was obtained by a boat generator, and auto batteries.

In 1913, George Bixby sold 16,000 acres of Rancho de los Palos Verdes to a group of investors led by Frank Vanderlip, retaining 1,000 acres for himself, which later subsequently evolved into Harbor City. Jotham Bixby died in 1916.

When World War II began, however, the Japanese families who were farming the Rancho Palos Verdes area were interned for the duration of the war; many were relocated to the internment camp at Manzanar, California. On February 1, 1942, Kumekuchi Ishibashi and his wife Take were taken to a detention camp for Japanese in Bismarck, North Dakota. In July, 1942, Kumekuchi’s family including his son Mas, Mas’ wife, Miye, along with their son Satoshi, who was seven years old at the time, and Mas’ brothers, George and Aki were interned at Poston, Arizona. In a little over one year, Kumekichi was able to reunite with his family in Poston. They then moved to Utah to farm for the duration of the war. Mas’ brother, George and Kay, served in the 442nd Regimental Infantry Combat Unit. This unit received more citations than any other outfit [of its size]. Miye Ishibashi sold strawberries on the side of the road and Mas farmed Rancho Palos Verdes for over 50 years, with the exception of the internment years. Their son Satoshi continued working with his father to farm rolling acres of barley and garbanzo beans for many of those years as well. Tomizo, Kumekichi’s brother, had four farming sons: Ichiro, James, Tom and Daniel and two daughters, Yukiko and Naomi. James Ishibashi’s farm is several miles down the road. His wife sold vegetables at “Annie’s stand,” serving the community for forty years. Tom Ishibashi farms on city-owned property next to Torrance Municipal Airport. [retired in 2006].

Machado Lake, located in the Ken Malloy Harbor Regional Park, is named after Jose Antonio Machado, who supervised the ranch of Jose Dolores Sepulveda. Machado’s ranch house stood on the shoreline of the lake on the highest point. After Jotham Bixby purchased the area, for a time the lake was known as the Bixby Slough. In 1971, the lake had been given the name Harbor Lake, but the lake was given its original name, Machado Lake, again in 1989 by the Los Angeles Recreation and Parks Commission. In the 1990’s, the Harbor Regional Park was named in honor of Ken Malloy, a San Pedro conservationist who spent many hours tending to the park’s wildlife and vegetation.

Rancho Sausal Redondo, Rancho Ajuaje de la Centinela and Rancho Centinela

In its earliest days, El Segundo, Manhattan Beach, and Hermosa Beach were part of the ten-mile ocean frontage of Rancho Sausal Redondo, which means “Round Clump of Willows.” In 1822, a year after Mexico had gained its independence from Spain, Antonio Ygnacio Avila was granted a permit to utilize grazing land totaling approx. 25,000 acres on what was to become Rancho Sausal Redondo, and on May 20,1837 received a land grant from Governor Juan Alverado for Rancho Sausal Redondo consisting of approx. 22,459 acres, which included the present-day cities of El Segundo, Gardena, Hawthorne, Hermosa Beach, Inglewood, Lawndale, Manhattan Beach, and Playa del Rey. On June 19, 1856, the U. S. District Court issued a decree of confirmation of title to Antonio Ygnacio Avila for Rancho Sausal Redondo.

Coach route between San Pedro and Pueblo Los Angeles

Where the city of Inglewood is today there was another, smaller, Mexican rancho called the Rancho Ajuaje de la Centinela, which means the “Sentinel of Waters.” This rancho was once part of the Rancho Sausal Redondo, and Ygnacio Machado had encroached on the land claimed by Antonio Avila, and was awarded provisional title to this land totaling approx. 2,200 acres at the same time that Antonio Avila received his land grant for the balance of the Rancho Sausal Redondo in 1837. In 1845, Machado traded the rancho to Bruno Avila, brother of Antonio Ygnacio Avila, for a small tract in the pueblo of Los Angeles. Bruno Avila, unfortunately, mortgaged his property at an interest rate of 6% per month, which was the standard interest rate at the time for personal loans, and unable to repay his debts, lost his property through foreclosure in 1857. Subsequent to this, the Rancho Ajuaje de la Centinela changed hands a number of times, eventually being acquired in 1860 for $3,000 by Sir Robert Burnett, a Scottish lord.

The Rancho Sausal Redondo property consisting of approximately 22,459 acres was purchased by Sir Robert Burnett on May 5, 1868 . when it was sold to him through probate court for $30,000 to pay debts accrued by the Avila estate (Antonio Ygnacio Avila had died in 1858). Burnett combined the two ranchos under the name of Rancho La Centinela.

In 1873, Burnett leased the land to Catherine Freeman with an option to buy, and Burnett returned to his native Scotland. When Catherine Freeman died in 1874, Daniel Freeman, her husband, used the land for sheep, horses and orchards with fruit, almonds and olives. When a severe drought occurred in 1875 and 1876, he received heavy loses. He turned to dry farming and did well with wheat and barley. In 1882, Freeman used his option to buy and he purchased 3,912 acres for the sum of $22,243. On May 4,1885, Freeman purchased the remainder of Rancho La Centinela for $140,000. Daniel Freeman was the last person to own all of Rancho La Centinela. Daniel Freeman eventually sold his land to several real estate developers.

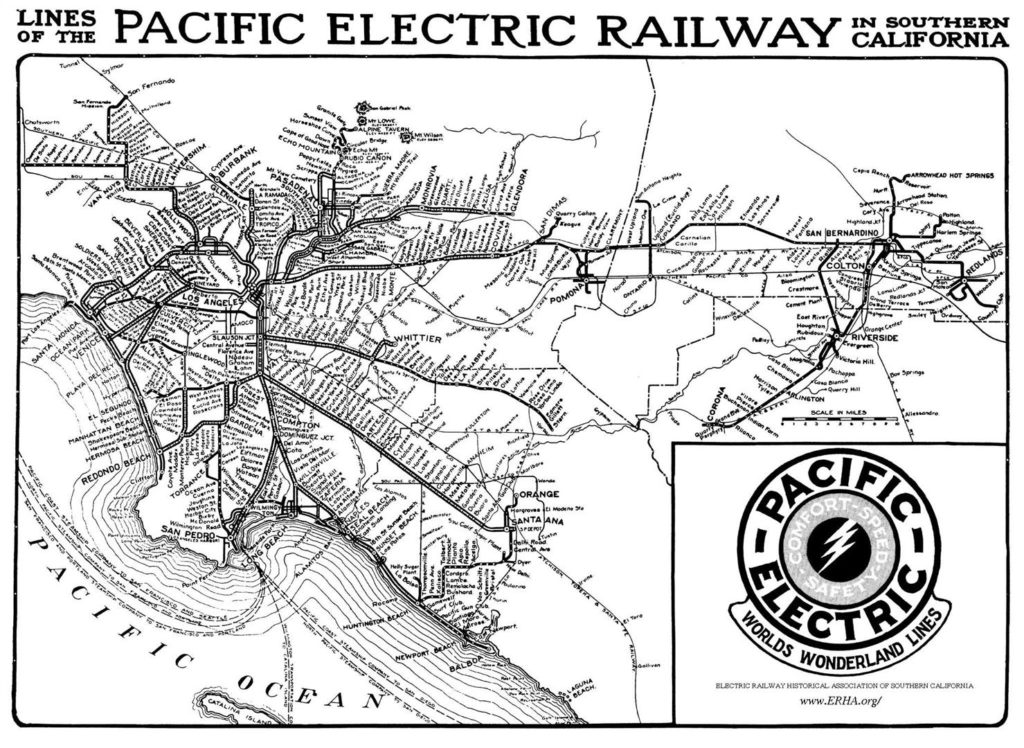

THE RED CAR LINE

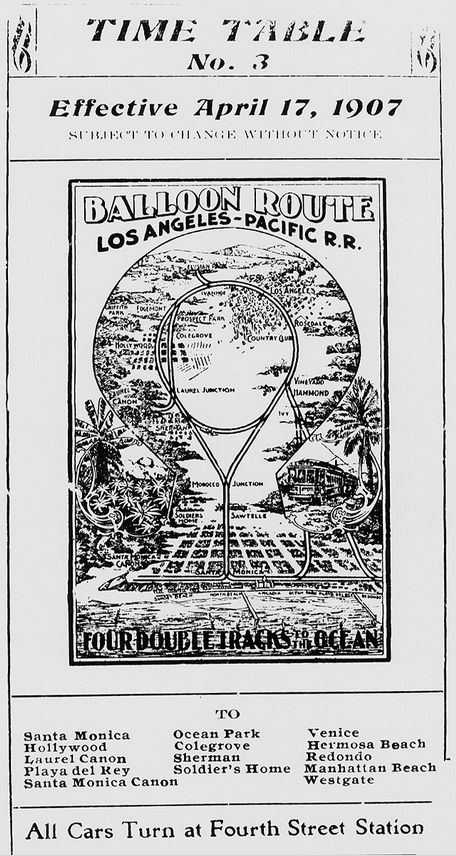

Henry Huntington was a very major real estate developer and public utility system tycoon in southern California. In 1901 Huntington formed the Pacific Electric Railway (“PE”) to serve his real estate development aims in the Los Angeles area. The largest of the suburban electric railways operating out of downtown Los Angeles in the early 1900s was not Huntington’s Pacific Electric but the Los Angeles Pacific (“LAP”).The heads of LAP also had extensive real estate development projects in Hermosa Beach, Manhattan Beach, Playa del Rey and Hollywood.

This very extensive railway ran streetcar lines out through Hollywood and suburban trolley lines to Santa Monica, Brentwood, and down the coast to Redondo Beach in what was called the “balloon route”.

In 1906 Edward Harriman, head of the Southern Pacific Railroad, gained control of the Los Angeles Pacific, and finally in 1910 he acquired Huntington’s PE, and in 1911 merged the two into Pacific Electric. At that time, all of the transit cars were painted red, leading to the moniker “red car line”.

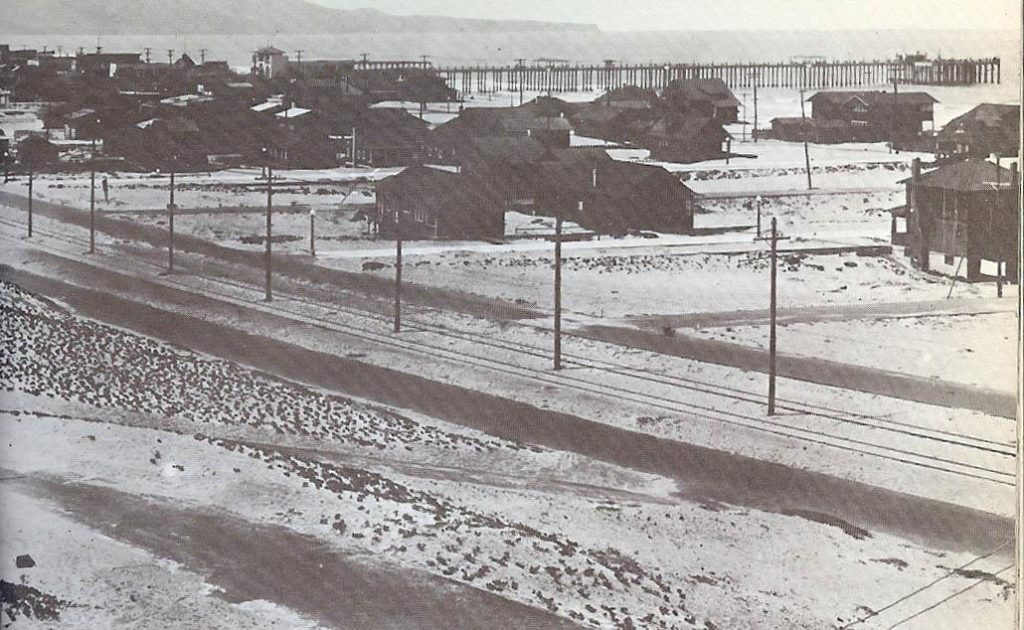

Red car along the ocean in Manhattan Beach The Redondo Beach via Playa Del Rey line was one of two electric railway lines to Redondo Beach operated by PE prior to World War II, the other running from LA through Gardena and Torrance. The route that had the higher ridership in the ’30s was the more scenic route down the coast from Playa Del Rey. This route led along the ocean from Playa del Rey through Manhattan Beach, then veering inland a bit through Hermosa Beach and ending in Redondo Beach. The developers of Palos Verdes in the early 1920’s planned for the extension of the red car line into the Peninsula and provided wide median strips in Valmonte and Lunada Bay to accommodate the red car lines. Red car tracks 1917 down Hermosa Ave in Hermosa Beach One of the major problems with PE as a passenger railway was that when developers originally invested in the trolley lines to serve their subdivisions, they were interested in providing only the minimum facilities they needed in order to sell real estate, and they were not intended to make money providing passenger service. And in fact the PE passenger operations as a whole never made a profit. The Southern Pacific was willing to accept the perennial operating losses of PE because SP made quite a bit of money off the freight business that was fed to SP by PE. In the ’20s to ’50s era, PE was the main hauler of freight to and from the combined ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles. Red car tracks and Red Car on left and Southern Pacific railroad tracks on right at Redondo Pier area The red car line also could never be called “rapid transit”, as it had to slog its way through surface street traffic. They were also very overcrowded. The trip from downtown Los Angeles to Redondo Beach took well over an hour. The increased ownership and convenience of the automobile spelled the demise of the Red Car. The red car line suffered severe operating losses throughout the 1930’s and were slowly replaced by bus service through the 1940’s. The Redondo Beach line was eliminated in 1940. The red car line is now only a nostalgic memory.

Highway Development

Road construction moved forward rapidly in the late 1950’s and through the mid 1960’s..Construction of Crenshaw Boulevard up a canyon from Palos Verdes Drive North to Silver Spur road commenced in mid June 1950. Construction of the extension of Crenshaw Blvd. to Palos Verdes South in the mid 1950’s triggered the disastrous Portuguese Bend Landslide which continues to this day. Construction of Hawthorne Blvd. through the Peninsula was completed in several segments. Hawthorne Blvd. was completed from Silver Spur Road to Crest in 1959. The segment from Palos Verdes Drive North to Silver Spur Road was completed in 1961. After several years of planning, the final segment extending Hawthorne Blvd. from Newton in Torrance to Palos Verdes Drive North was completed in 1965.

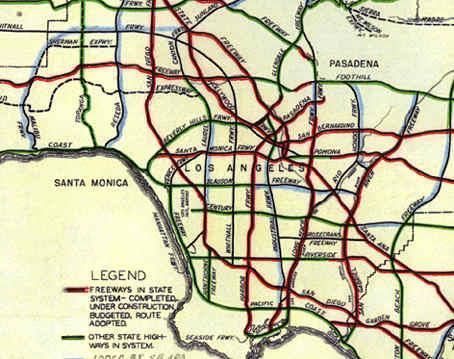

The original masterplan for the Southern California freeway system included what was known as the Ocean Freeway or the Pacific Coast Freeway, which was to have run along the coast, swinging inland through Redondo Beach and Torrance and connecting to the Harbor Freeway, and extending through Long Beach. Another freeway connecting to the San Diego Freeway roughly following to the east of Hawthorne Boulevard had also been proposed. In 1968, several alternative alignments of what was called the “Hawthorne Freeway” (route 107) were considered. These included routes connecting from the San Diego Freeway roughly following just to the east of Inglewood Boulevard, and as far west as Prospect through Manhattan Beach and Redondo Beach, then swinging east along the Palos Verdes Peninsula foothills, and terminating at Vermont Ave. (with a planned connection with the Harbor Freeway when the Ocean Freeway was to be extended through Long Beach). The most southernmost route considered would have demolished some homes in Rolling Hills Estates, in the neighborhoods of Montecito, Empty Saddle, and the Empty Saddle Club. Due to funding constraints, and neighborhood opposition, these freeways, of course, were never constructed.

Original Master Plan for Southern California Freeway System circa 1958

Also: Click for: Palos Verdes Secrets & Little Known Facts

Click on the following links for the history of individual cities in the South Bay Los Angeles beach communities:

HISTORY OF PALOS VERDES ESTATES

HISTORY OF RANCHO PALOS VERDES

HISTORY OF ROLLING HILLS ESTATES AND ROLLING HILLS

COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

Graphics, content and html coding may not be reproduced or copied in any way with out written permission from Maureen Megowan All html coding, layout and original content and graphics are copyrighted – Maureen Megowan and may not be used, copied or reproduced on another web site. Maureen Megowan makes no guarantees or warranties as to the information provided herein

Sources:

Historic Adobes of Los Angeles County 1997 John R. Kielbasa

Historical photos courtesy of the Palos Verdes Library h

http://www.laokay.com/halac/DominguezRanchAdobe.htm

http://ci.carson.ca.us/content/department/about_carson/RanchoDominguez.asp

“A History of Los Palos Verdes Rancho 1542-1925, A Thesis Presented to the Dept. of History-The University of Southern California, by Mary Sue Thatcher, dated May 1, 1923”

“Time and the Terraced Land” by Augusta Fink

Historical Data for Palos Verdes Publicity , Prepared for Great Lakes Carbon Corp. by Stanford Research Institute

The Palos Verdes Peninsula: A History , by Carmen Marinella, 9/93

The Rancho San Pedro , by Robert Cameron Gillingham

History of Rancho Sausal Redondo, Rancho Ajuaje de la Centinela and Rancho Centinela: h

http://www.laokay.com/halac/CentinelaAdobe.htm

http://history90266.org/DuncanFolklore.htm

http://supreme.justia.com/us/115/102/case.html

Pictures: http://contentdm.califa.org/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/p3003coll32&CISOPTR=136&CISOBOX=1&REC=19

I am indebteded to Delane Morgan, author of The Palos Verdes Story. I would highly recommend purchasing her book, which includes numerous historical photos and a much more detailed history of the Palos Verdes Peninsula. This book may be purchased at the shop Nantucket Crossing located in the Town & Country Shopping Center on Silver Spur Road in Rolling Hills Estates.

CLICK HERE TO RETURN TO MAUREEN MEGOWAN REAL ESTATE HOME PAGE